From the President: The Great Leap

A long career as a professional soldier had taught him much about storytelling and stout drink, both of which he shared liberally. Sipping baijiu from a small ceramic cup, the old man recounted his grim introduction to the military as a teenager in the infantry during the Second Sino-Japanese War. It was his job to liberate Beijing from the occupying Japanese. Over the next hour he raced through 70 years of serving witness to profound local events as a world war gave way to a Cold War and then to the Cultural Revolution, Tiananmen square demonstrations, economic good times, and the Olympics.

At the end of a too short stay, he thanked me for listening. I thanked him for his stories and for welcoming us into his home. As we rose to leave, he asked that I tell people about the wonderful program that brought his family doctor and nurse to their small apartment, each Thursday. Those visits enabled him, at age 88, and his wife, age 85 and disabled by a stroke, to remain in their own home. I promised him that I would do my best to tell that story. So, here goes.

Prof Rich Roberts on a home visit in Beijing with (from l to r): nurse, Ding Lan; patient, Duan Jujie; Dr Li Jing; patient, Wang Jing; home help person; Prof Roberts.

In April, I made my tenth trip to China over the past 20 years. My primary reason for this visit was to speak at the 9th Beijing Symposium on Family Medicine. The annual conference is sponsored by FuXing Hospital, one of nine teaching hospitals affiliated with Capital Medical University (CMU). There are five medical schools in Beijing: CMU, Peking University Health Science Center, Tsinghua University School of Medicine, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, and Peking Union Medical College, which was founded by American and British missionaries, in 1906, and funded by The Rockefeller Foundation and its China Medical Board. CMU is also designated by the Ministry of Health (MoH) as the national training center for general practice. During this visit, I learned more about general practice in China than I had with any previous visit.

In some ways, the story of modern general practice in Beijing began in 1994 in the XiChing district. On the western edge of the six districts of central Beijing (there are an additional 10 districts in greater Beijing), XiChing is home to about 800,000 people and 24 hospitals. In 1994, Dr Xueping Du began an initiative in XiChing to put more health services in the community, which culminated, in 1996, with the establishment of the Red Apple Community Health Service (CHS) Centre (Station). These efforts

improved patient satisfaction and reduced hospitalization for various chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease.

A program to train general practitioners was started by FuXing Hospital, in 2000, with the construction of the YueTan CHS Centre, a five-story building with several dozen general doctors, including traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) practitioners. YueTan is linked to nine neighborhood stations, each staffed by 1–4 doctors with oversight by a neighborhood committee. The patient base at YueTan CHS Centre has increased from 8,700 to more than 300,000, over the past 15 years. XiChing District now has 15 CHS centers and about 80 neighborhood stations.

The program at YueTan has grown way beyond local health services. Under Dr Du’s leadership, they reach out to conduct training programs in more remote parts of China, such as Outer Mongolia. They also convene the annual Beijing symposium, which brings together more than 1,000 nurses and doctors in primary health care, for a week each spring. In recognition of her extraordinary vision and accomplishments, Dr Du was named the winner of the 2010 Sasakawa Health Prize, the only WHO award focused on primary health care.

The terms ‘general practitioner’, ‘general medicine doctor’, and ‘family doctor’ are used interchangeably at FuXing. Following five years in medical school, the training of a general practitioner in the FuXing 3+2 program involves three years in the hospital followed by two years in the CHS Centre or a neighborhood station. There is also a shorter 2+1program that trains what are known variously as community, health care, or public health doctors who are responsible for the health care of children and reproductive age women.

During my week in Beijing, I visited with numerous leaders in the MoH, CMU, and FuXing Hospital. The best days however, were those spent with family doctors attending their patients. In addition to consultations at YueTan CHC Centre, I observed doctors at three neighborhood stations, on home visits, at Yin Ling Nursing Home, and at a primary school.

Prof Rich Roberts sits in on a consultation. Prof Roberts with (from l to r): Dr Li Xiao Xiao, Dr Wu Lin, and patient Lu Ming.

Consultations were usually conducted in an open carrel, with clinical staff, other patients, or family members walking by, or sometimes listening in. Examinations were usually limited to assessing vital signs and occasionally listening to heart or lungs. Some doctors saw 60-70 patients in seven hours of consultation. Two key factors responsible for so many of the visits per doctor were medications for chronic diseases like hypertension, which had to be dispensed each month by the doctor to the patient, and paperwork, which had to be completed for the patient, or a family member. Much of the session, especially for younger doctors, was spent focused on the computer.

The technology and facilities I observed in the hospital and health centers were modern and clean. There seemed to be ready access to laboratory and imaging studies, although most usually required referral to the hospital. Most patients had social insurance (UEBMI Urban Employee’s Basic Medical Insurance), through the government. Patients were responsible for the first 1,800 Renminbi (1 RMB or yuan equals about USD 0.15), then insurance covered about 85% of costs. Patients had a maximum annual out-of-pocket cost for outpatient services of 20,000 RMB.

The professionals I encountered were well trained and dedicated to their patients. Some doctors would whisper to me that they gave their mobile numbers to certain patients to save them after hours visits to the hospital. I was most impressed with their technical knowledge and genuine compassion for their patients.

While general medicine has come a long way in China, it still has a long way to go. Patients are often compartmentalized by age or ailment, rather than having the same trusted family doctor care for them across their life continuum. After completing three years of rigorous training in hospital, family doctors disconnect themselves from inpatient care once they enter practice. Doctors and nurses work in a system that bogs them down with administrative tasks, such as dispensing medications or completing paperwork, when that time would be better spent focused on patient needs.

To their credit, Chinese leaders and health professionals acknowledge that they need and want to do more, and better. They asked repeatedly about potential assistance with train the trainer programs, guidelines development, expanded services such as mental health in the community setting, and research. While there has been international collaboration in medical education and research for many years in China (CMU alone has formal relationships with more than two dozen institutions from other countries), it has been only over the past few years that such relationships have centered on general practice.

My university department began a relationship with the FuXing training program about the time it started. Led by Prof Ken Kushner, PhD, our department and Dr Du’s program have exchanged students, trainees, and faculty; have seen much of China and the USA together; and have published jointly. We have spent time in each others’ homes and come to know each others’ families. These personal and enduring relationships have proved to be an essential part of our successful collaboration.

Heraclitus reminded us that we cannot jump twice into the same river because it constantly changes. That is my sense of China. In Beijing the pace of change is measured by the number of construction cranes and Ring Roads. During my previous visit a few years before the Olympics, there were four ring roads in use, now there are six. The pressure of population and the rush to economic development create an incredible pace of change. With the world’s largest and fastest growing aged population, and with nearly one third of Chinese children at risk for obesity, China will need to develop lifelong strategies to promote better health and longer productivity. I believe that family doctors and primary health care can be part of that solution.

On several occasions over the past two decades, it has been my honor to meet with high level officials of the MoH and other health leaders. Each time, I was told that China planned to train 1 million family doctors. Each time, it appeared as though little progress had been made since my previous visit. This time however, I was given a more modest projection that the plan is to increase the number of trained GPs from 60,000 to 210,000 by 2015. This time, I came away with a greater sense of commitment to and progress of Family Medicine in China.

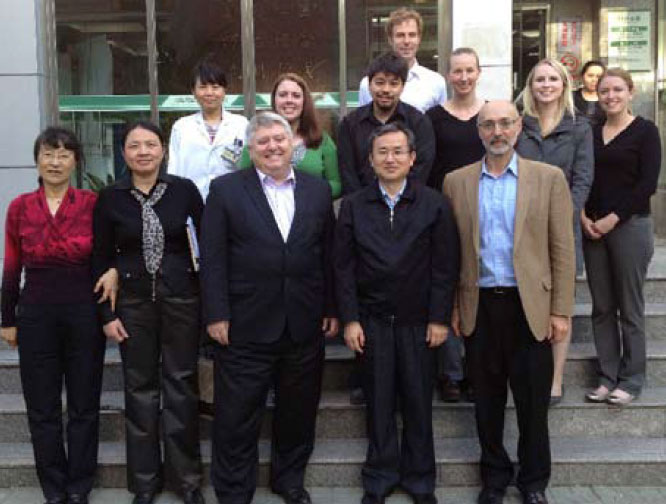

Met in China are (front row from l to r)Dr Du (wearing a red top), Chen Xinyu MD MPH, Director Department of Medical Sciences, Technology and Education, MoH, PRC; Prof Roberts; Jin Shengguo PhD, Deputy Director General Department of Medical Sciences, Technology and Education, MoH, PRC; Prof Kushner. In the second row Dr Ding, associate director in the program that Dr Du leads (wearing a white lab coat). The other people in the back rows are medical students from the University of Wisconsin, USA.

My fear for China leaders is not that they will think too large, but that they will think too small. I believe that China’s growing wealth and ability to accomplish breathtaking change in a short period of time create a unique moment of opportunity. If they can transform their health system into one built on the principal that every member of Chinese society should have a trusted family doctor providing the most comprehensive services possible, then I believe that they will make a great leap forward to the world’s best health care system.

Professor Richard Roberts

President

World Organization of Family Doctors