From the President: Turning tasks to TRUST

Español

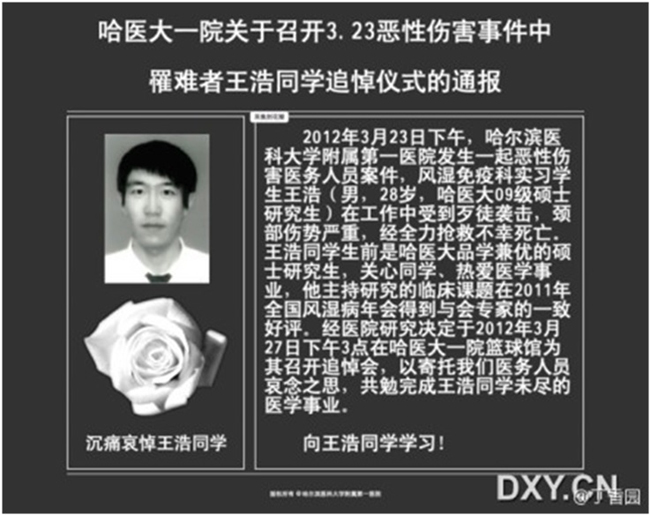

I spoke recently at the 11th annual Beijing Symposium on Family Medicine. My remarks began with the story of Dr Wang Hao, a young physician at Harbin Medical University’s No. 1 Hospital. On 23 March 2012, Li Mengnan, a teenage patient of the Hospital, broke into the rheumatology and immunology department, slit the throat of Dr Wang, and stabbed three other doctors who were also in the room.

Obituary of Dr Wang Hao, age 28, 23 March 2012

Obituary of Dr Wang Hao, age 28, 23 March 2012

The motive for the killing was a tragic misunderstanding. Li had asked Dr Zhao Yanping, the deputy director of the department, to prescribe infliximab (Remicade) for his ankylosing spondylitis. Dr Zhao responded that Li first needed to have his tuberculosis treated to avoid infliximab toxicity. Li misunderstood and concluded that he was not going to receive any treatment. Dr Wang and colleagues were the unfortunate victims of that misunderstanding.

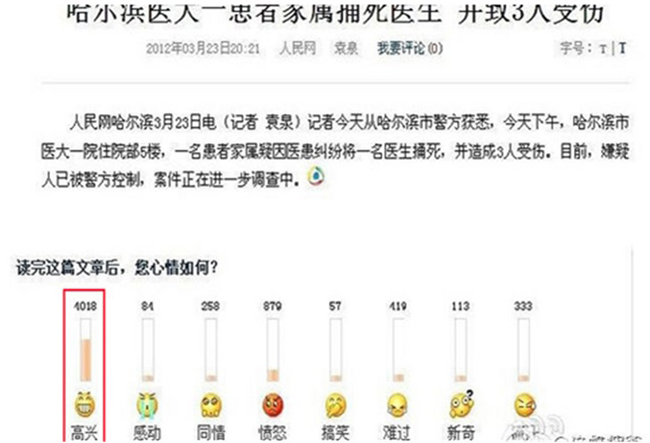

Shortly after the killing, the website of the People’s Daily posted an on-line survey asking readers to indicate how they felt about the murder. About two out of three respondents selected the happy icon to describe their feelings about Dr Wang’s death. The survey was removed from the website after one day. The young assailant was sentenced to life in prison on 19 October 2012. Li avoided the death penalty because he was 17 years old and not considered an adult at the time of the crime.

People’s Daily on-line survey on response to Dr Wang’s murder, 23 March 2012

People’s Daily on-line survey on response to Dr Wang’s murder, 23 March 2012

It seems unlikely that any of the People’s Daily survey respondents knew or held anything against Dr Wang. By all accounts, he was a dedicated and capable young physician. More likely is that the survey caught a glimpse of some of the frustration voiced increasingly by Chinese patients. The government estimated that in 2010 there were 17,000 violent incidents involving 70% of public hospitals.

Some of the factors influencing violence against health workers may be peculiar to China, such as relatively low physician pay that creates pressures to accept red envelopes with cash or industry kickbacks. The violence against Chinese physicians however, is only a dramatic example of worrisome trends in health care that are common to most countries and most health care systems. These trends reflect an increasingly mechanistic rather than holistic approach to health care, an obsession with biometric measures rather than outcomes that are meaningful to patients, and an emphasis on disease rather than health. In short, while our technical and technological capabilities have increased dramatically, our trust in the motives and agenda of health care has decreased concomitantly.

The focus of doctors has shifted from seeking cure, relieving suffering, and providing comfort to accomplishing tasks and completing checklists. More resources and energy are dedicated to managing populations (usually those with chronic and expensive conditions), with relatively less effort spent learning about the concerns, values, and goals of the patient. The irony is that until our science is dependably predictive for every patient and until every patient chooses the same goals, our inability to nurture trust with the patient will keep us from successfully accomplishing our tasks or completing our checklists.

I propose that an essential and explicit goal of health care should be to foster TRUST: time, reliability, unity, skill, and transparency.

Time

Patients need and deserve our time with them. Ideal is face time, which is valued more by people than email, texting, or videoconferencing. Virtual communication will undoubtedly become more generally used and accepted. Time getting to know the patient, and having them get to know us, is crucial for TRUST. This vital activity is not and should not be easily delegated. It is often said that the top 3 concerns of primary health care should be access, access, access. Without providing ready access, patients must turn to any available resource when problems arise, such as emergency departments or hospitals. For certain individuals with certain conditions and in certain settings, these other resources will be exactly the right place for care, but not for most people with most conditions in most situations. The lack of awareness of their individual needs and expectations, and the greater risk for over-utilization or iatrogenesis, make these other places more costly and potentially dangerous for patients than seeing their family doctor.

Reliability

People value consistency and dependability. There are the apocryphal stories of patients remaining loyal to grumpy doctors because they are consistently grumpy and their behaviors are predictable. Punctuality is also a sign of reliability and signals respect for the patient’s time. This attribute of TRUST – reliability - is where checklists and care pathways come into play. When all are agreed, including most importantly the patient, that a certain plan of action should be pursued, then a more reliable care system will emerge as more effective and efficient strategies are developed for accomplishing those plans.

Unity

A critically important part of TRUST is to establish shared expectations between doctors and patients as to the goals to be achieved and the methods and time to achieve them. These shared expectations create unity of purpose and produce a stronger relationship built on common goals and mutual responsibilities. In the sad case of Dr Wang, it is apparent that at best there was insufficient communication about the plan of care and that at worst there was no explicit or trusted plan of care. The most trusted and powerful patient-doctor relationships develop when patients are convinced that their doctors have their best interests at heart and will do their best to help them.

Skill

TRUST is about more than satisfactory relationships. Patients expect their family doctors and other health professionals to possess diagnostic and therapeutic skills that reflect currency and competence. Health professionals often fret that patients expect perfection. They do not. They do expect a sincere effort using the most appropriate knowledge and resources given their specific circumstances.

Transparency

Perhaps the most important element of TRUST is transparency. Patients want clarity about what needs to happen for their condition and why. The extent of disclosure will vary depending on the patient’s age, desire or capacity to know, and cultural expectations. Related to the issue of disclosure about diagnosis and treatment is the question of self-disclosure by the doctor. People are more likely to TRUST another when they have a better sense of that other person. It can be quite challenging to accomplish self-disclosure without misleading the patient about the doctor’s intention to strengthen a professional, rather than personal, relationship and without turning the doctor into the center of attention. Transparency becomes especially important when an error or unexpected or unwanted outcome has occurred. Seeking the patient’s perceptions on what happened and what went wrong demonstrates respect and concern. Briefing the patient with a clear accounting of what happened and why provides a reality check for what was possible given current knowledge and resources. A useful approach is to employ “magical” language that acknowledges the magical thinking that people often use to explain and comprehend their current situation. An example might be, “I also wish you did not have diabetes, but we can work together to reduce its effect on your health.” When a mistake in care has occurred, transparency makes it possible to express empathy about the undesired result and to seek forgiveness when appropriate.

The ability to develop and maintain TRUST is essential for family doctors. Without TRUST, patients will doubt professionals’ motives, adherence to recommendations will be less dependable, and outcomes will suffer. Patients are unlikely to TRUST the health care system unless they TRUST the individual professionals from whom they seek care. The best way to build TRUST in the system is one patient at a time.

Professor Richard Roberts

President

World Organization of Family Doctors